Variational framework for perception and action

Introduction

This post presents a mathematical formalism of perception, action, and learning, based on the framework of variational inference. It appears that a variational formalism has the potential to shed light on the ad-hoc choices used in practice; we will see that the notion of entropy regularization (as in SAC) and penalizing policy drift (as in PPO) emerge naturally from this framework. Further, this formalism provides a model-based method of reinforcement learning, featuring both representation learning & action-selection on the basis of these learned representations, in a manner analogous to “World Models” [3]. We will also see that, under certain assumptions, we obtain an alternative credit assignment scheme to backpropagation, called predictive coding [6, 7]. Backpropagation suffers from catastrophic interference [4] and has limited biological plausibility [5], whereas predictive coding – a biologically-plausible credit assignment scheme – has been observed to outperform backpropagation at continual learning tasks – alleviating catastrophic interference to some degree [6] – and at small batch sizes [8] (i.e. biologically relevant contexts).

A brief background on reinforcement learning methods can be found in the Appendix.

Related work. The framework presented here differs from previous work. [1] describes an agent’s preference via binary optimality variables whose distribution is defined in terms of reward, from which they are able to justify the max-entropy framework of RL, however their framework does not result in a policy drift term (as in PPO). In contrast, for the formalism presented here, we will see that it is most natural to represent an agent’s preferences via a distribution over policies (defined in terms of value), from which a policy drift term and an entropy regularization term naturally emerge. There is also the topic of active inference [9] which aims to formulate action-selection as variational inference, however it appears that central claims – such as the minimization of the “expected free energy” – lack a solid theoretical justification, as highlighted by [10, 11].

Variational framework for perception & action

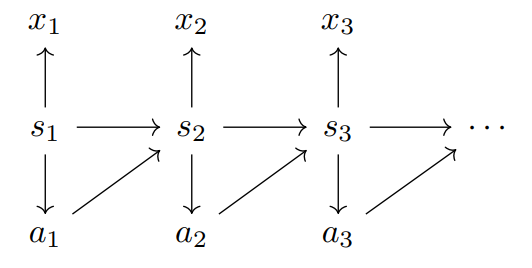

We will consider the following graphical model,

where \(s_t\) represents the environment’s (hidden) state, \(x_t\) a partial observation of this state, and \(a_t\) an action, at time \(t\). For simplicity we have made a Markov assumption on how the hidden states evolve. The dependency \(s_t \to a_t\) is a consequence of this Markov assumption, with the optimal action \(a_t\) (optimality defined further below) ultimately depending only on the current environment state \(s_t\), independent of previous states \(s_{<t}\) (given \(s_t\)).

The associated probabilistic decomposition (up to time \(t\)) is

\[p(s_{1:t}, x_{1:t}, a_{1:t}) = \prod_{\tau=1}^{t} p(s_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau-1}, a_{\tau-1}) p(x_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}) p(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})\]where \(p(s_1|s_0, a_0) \equiv p(s_1)\). We can interpret:

- \(p(s_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau-1}, a_{\tau-1})\) as describing the environment’s Markov transition dynamics.

- \(p(x_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})\) as describing the lossy map from hidden state to partial observation.

- \(p(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})\) as describing the ideal/optimal action distribution given the state \(s_{\tau}\), where optimality is defined with respect to a value system (described further below).

To provide a Bayesian framework for action, we wish to frame the objective of an agent as performing inference over this graphical model. Since an agent will have access to information \((x_{1:t}, a_{<t})\) at time \(t\), we wish to frame action selection of the next action \(a_t\) as the process of computing/sampling from

\[p(a_t\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t}) \equiv \int ds_t \; p(s_t\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t}) p(a_t\mid s_t)\]i.e. we can view action selection as the process of inferring the underlying state \(s_t \sim p(s_t\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})\), and then inferring the associated action \(a_t \sim p(a_t\mid s_t)\). But how do we appropriately define \(p(a_t\mid s_t)\) to represent an “ideal” agent? Naively we may consider \(p(a_t\mid s_t)\) to be a point-mass/Dirac-delta distribution centered at the optimal action \(a^{*}(s_t)\), however this does not provide a convenient notion of Bayesian inference. Instead we will consider a smoothed version that places the most weight on the optimal action \(a^{*}(s_t)\), but also places non-zero weight on other actions, in a way that is correlated with an action/policy’s value. In order to define \(p(a_t\mid s_t)\) to satisfy this notion, we will assume that \(p(a_t\mid s_t)\) takes the form of a mixture distribution, introducing a policy variable \(\pi\) and writing,

\[p(a_t\mid s_t) = \int d\pi \; p(a_t, \pi\mid s_t) = \int d\pi \; p(\pi\mid s_t) \pi(a_t\mid s_t)\]where we write \(\pi(a_t\mid s_t) \equiv p(a_t\mid s_t, \pi)\).

- The reason for assuming the form of a mixture distribution and introducing the policy variable \(\pi\) is because it is unclear how the goodness of a single action \(a_t\) would be defined otherwise. Its goodness is based on how the future plays out, which requires taking some additional future actions, and the policy variable \(\pi\) takes the role of determining these future actions, allowing for a well-defined notion of value.

A notable property of a mixture distribution is that we can write \(p(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}) = \mathbb{E}_{p(\pi\mid s_{\tau})}[\pi(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})]\), which – as we will see later – allows us to apply a variational bound. We then introduce a value system \(V_{\pi}(s)\), describing the value of policy \(\pi\) starting from the state \(s\). We can consider a Boltzmann preference over policies based on this value system,

\[\begin{equation} \label{eqn:boltz} p(\pi\mid s_t) \propto \exp(\beta V_{\pi}(s_t)) \quad \quad (1) \end{equation}\]where, as typical in the context of RL, we define the value as,

\[V_{\pi}(s_t) = \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi)}\left[\sum_{\tau=t}^{\infty} \gamma^{\tau-t} R(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau})\right]\] \[\text{with} \; \; \; p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi) = \prod_{\tau=t}^{\infty} \pi(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}) p(s_{\tau+1}\mid s_{\tau}, a_{\tau})\]for a discount factor \(\gamma \in [0, 1]\). Note that \(\beta = \infty\) corresponds to taking an argmax over \(V_{\pi}(s_t)\), representing “perfect rationality”. Finite \(\beta\) corresponds to “bounded rationality”, placing weight on policies that dont perfectly maximize \(V_{\pi}(s_t)\).

- We will leave the remaining distributions – \(p(s_t\mid s_{t-1}, a_{t-1})\) and \(p(x_t\mid s_t)\) – implicit, but in practical implementation, we can choose them as Gaussians parameterized by neural networks.

Variational inference. However, even assuming that we have direct access to all relevant distributions (which we dont), computing the integral of Equation (1) will be intractable as we expect \(s_t\) to be high-dimensional. As a result, we cannot perform exact Bayesian inference and so must utilize an approximate scheme of Bayesian inference. The approximate scheme we will consider is variational inference: at time \(t\) an agent has access to information \((x_{1:t}, a_{<t})\), and we will consider minimizing (with respect to \(p\)) the model’s corresponding surprise \(-\log p(x_{1:t}, a_{<t})\) by instead minimizing (with respect to \(p\) and \(q\)) the variational bound \(F(x_{1:t}, a_{<t})\),

\[-\log p(x_{1:t}, a_{<t}) \leq F(x_{1:t}, a_{<t}) := D_{\text{KL}}(q(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})\mid \mid p(s_{1:t}, x_{1:t}, a_{<t}))\](a consequence of Jensen’s inequality) where we have introduced the variational/approximate distribution \(q\). \(F\) is commonly called the variational free energy (VFE). Variational inference considers minimizing this upper bound \(F(x_{1:t}, a_{<t})\) on surprisal, rather than minimizing the surprisal itself (which is intractable to do). We will use the shorthand \(F_t \equiv F(x_{1:t}, a_{<t})\).

When the VFE \(F_t\) is perfectly minimized with respect to \(q\), with \(q(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t}) = p(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})\), then the VFE is exactly equal to the surprisal,

\[F_t = -\log p(x_{1:t}, a_{<t})\]in which case further minimizing \(F_t\) with respect to \(p\) achieves our original goal. This is the basis of the variational EM algorithm: at time \(t\),

- E-step: Minimize \(F_t\) with respect to \(q\) until convergence to \(q = q^{*}\).

- M-step: At fixed \(q = q^{*}\), minimize \(F_t\) for one/a few steps with respect to \(p\).

In practice, we will implement these steps via gradient-based minimization, as will be described in more detail later. The E-step cannot be performed until convergence in practice but we will typically perform many more E-steps than M-steps.

In general we can write \(F_t\) as

\[\begin{align*} F_t = &\sum_{\tau=1}^{t} \mathbb{E}_{q(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[\underbrace{-\log p(s_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau-1}, a_{\tau-1})}_{\text{perception}} \underbrace{-\log p(x_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})}_{\text{prediction}}]\\ &+ \sum_{\tau=1}^{t-1} \mathbb{E}_{q(s_{\tau}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[\underbrace{-\log p(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})}_{\text{action}}]\\ &\underbrace{-H[q(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})]}_{\text{entropy regularization}} \end{align*}\]As seen above we chose \(p(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})\) to be a mixture distribution, but the log of a mixture distribution (the “action” term above) lacks a nice expression. However, we can apply a variational bound on this term with respect to \(q(\pi\mid s_{\tau})\) by noting that \(p(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})\) is an expectance,

\[p(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}) = \mathbb{E}_{p(\pi\mid s_{\tau})}[\pi(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})] = \mathbb{E}_{q(\pi\mid s_{\tau})}\left[\frac{p(\pi\mid s_{\tau})}{q(\pi\mid s_{\tau})} \pi(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}) \right]\]and hence we can perform a variational bound (via Jensen’s inequality),

\[\begin{align*} -\log p(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}) &\leq D_{\text{KL}}(q(\pi\mid s_{\tau})\mid \mid p(\pi\mid s_{\tau})) + \mathbb{E}_{q(\pi\mid s_{\tau})}[-\log \pi(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})]\\ &= \mathbb{E}_{q(\pi\mid s_{\tau})}[-\log p(\pi\mid s_{\tau}) - \log \pi(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})] - H[q(\pi\mid s_{\tau})] \end{align*}\]Overall, this results in a unified objective for perception and action:

\[\begin{align} \label{eqn:freeenergy} F_t &= \sum_{\tau=1}^{t} \mathbb{E}_{q(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[\underbrace{-\log p(s_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau-1}, a_{\tau-1})}_{\text{(a)}} \underbrace{-\log p(x_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})}_{\text{(b)}}]\nonumber \\ &+\sum_{\tau=1}^{t-1} \mathbb{E}_{q(\pi\mid s_{\tau}) q(s_{\tau}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[\underbrace{-\log p(\pi\mid s_{\tau})}_{\text{(c)}} \underbrace{-\log \pi(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})}_{\text{(d)}}] \quad \quad \quad (2)\\ &\underbrace{- H[q(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})]}_{\text{(e)}} + \sum_{\tau=1}^{t-1} \mathbb{E}_{q(s_{\tau}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[\underbrace{-H[q(\pi\mid s_{\tau})]}_{\text{(f)}}] \nonumber \end{align}\]where

- (a) and (b) represent the process of perception and prediction/representation learning.

-

(c) represents achieving the agent’s preference. In the case of Equation (1) this term corresponds to value maximization, with

\[-\log p(\pi\mid s_{\tau}) = -\beta V[\pi\mid s_{\tau}] + \log Z(s_{\tau})\]for normalizing constant \(Z(s_{\tau})\).

- (d) penalizes policy drift, by incentivizing \(q(\pi\mid s_{\tau})\) to favour policies \(\pi\) that fit previously taken actions \(a_{<t}\).

- (e) and (f) are entropy regularization terms, for perception and action-selection respectively.

Note that (d) and (f) achieve the same role as policy clipping in PPO, and the entropy regularization in SAC, respectively. Note that entropy regularization in SAC has been previously justified via a variational framework [1], but with differences to the framework presented here (as described at the beginning).

Under Equation (1), term (c) reduces to the expected value which is exactly what the field of reinforcement learning is concerned with. An overview of reinforcement learning methods is included in the Appendix.

Internal structure of hidden states. We can include additional structure on the hidden state \(s\) by generalizing to an arbitrary DAG topology for the hidden state \(s_t = (s_t^1, \ldots, s_t^N)\), where \(s_t^n\) is the state of node \(n\) at time \(t\). For a general DAG, we have

\[p(s_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau-1}, a_{\tau-1}) = \prod_{n=1}^{N} p(s_{\tau}^{n}\mid s_{\tau}^{\mathcal{P}(n)}, s_{\tau-1}^{n}, a_{\tau-1})\]where \(\mathcal{P}(n) \subset \{1, \ldots, N\}\) denotes the parent indices for the \(n\)th node. Further, \(p(x_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}) = p(x_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}^{\mathcal{P}(0)})\), and we will denote \(s_t^0 \equiv x_t\). Note that we have implicitly made a locality assumption of \(p(s_{\tau}^{n}\mid s_{\tau}^{\mathcal{P}(n)}, s_{\tau-1}, a_{\tau-1}) = p(s_{\tau}^{n}\mid s_{\tau}^{\mathcal{P}(n)}, s_{\tau-1}^{n}, a_{\tau-1})\).

- Conditioning \(s_{\tau}^{n}\) on \((s_{\tau-1}^n, a_{\tau-1})\) accounts for temporal dynamics.

- And conditioning on \(s_{\tau}^{\mathcal{P}(n)}\) accounts for local interaction effects between nodes.

In this case we can write Equation (2) as

\[\begin{align} \label{eqn:dagfreeenergy} F_t &= \sum_{\tau=1}^{t} \sum_{n=1}^{N} \mathbb{E}_{q(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[\underbrace{-\log p(s_{\tau}^n\mid s_{\tau}^{\mathcal{P}(n)}, s_{\tau-1}^n, a_{\tau-1})}_{\text{(a)}}]+\sum_{\tau=1}^{t} \mathbb{E}_{q(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[\underbrace{-\log p(x_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}^{\mathcal{P}(0)})}_{\text{(b)}}]\nonumber \\ &+\sum_{\tau=1}^{t-1} \mathbb{E}_{q(\pi\mid s_{\tau}) q(s_{\tau}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[\underbrace{-\log p(\pi\mid s_{\tau})}_{\text{(c)}} \underbrace{-\log \pi(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})}_{\text{(d)}}]\\ &\underbrace{- H[q(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})]}_{\text{(e)}} + \sum_{\tau=1}^{t-1} \mathbb{E}_{q(s_{\tau}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[\underbrace{-H[q(\pi\mid s_{\tau})]}_{\text{(f)}}] \nonumber \end{align}\]We may restrict action selection to a particular node, e.g. \(\pi(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}) = \pi(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau}^N)\).

Inclusion of entropy terms. Note that the entropy regularization terms (e) and (f) are not present if we consider the cross-entropy objective

\[\mathbb{E}_{q(s_{1:t}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[-\log p(s_{1:t}, x_{1:t}, a_{<t})]\]instead of \(F_t\), but otherwise this objective and \(F_t\) are equivalent. This appears necessary if we wish to consider a point-mass distribution over policies \(q(\pi\mid s_{\tau}) = \delta(\pi - \pi_{\phi})\) as otherwise the entropy terms become infinite.

Predictive coding. Predictive coding [6, 7] is a special case of variational inference under a hierarchical latent topology that results in a local, and hence biologically-plausible, credit assignment scheme – this contrasts with backpropagation which has limited biological plausibility [5]. It has been observed that predictive coding alleviates catastrophic interference to some degree [6], which is a known problem with backpropagation [4].

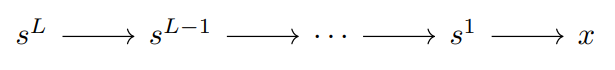

Predictive coding, in its typical formulation, ignores temporality and action. We will consider extending predictive coding to include both of these aspects later. In this context, with a hierarchical topology, the relevant graphical model is

with \(s = (s^1, \ldots, s^L)\) and decomposition

\[p(s, x) = p(s^L) \prod_{l=1}^{L} p(s^{l-1}\mid s^l)\]where \(s^0 \equiv x\). Predictive coding makes two further assumptions:

- \(p\) is Gaussian,

with \(\mu_l(s^l) = \mu_l(s^l; \theta_l)\), where \(\theta = (\theta_1, \ldots, \theta_L)\) and \((\hat{\mu}, \hat{\Sigma})\) parameterize \(p\).

- \(q\) is point-mass,

where \(z = (z_1, \ldots, z_L)\) parameterize \(q\).

We can interpret \(z\) as the fast-changing synaptic activity, and \(\theta\) as the slow-changing synaptic weights. This interpretation is supported by the variational EM algorithm, which indeed updates the parameters of \(q\) (in this case, parameter \(z\)) at a faster timescale than the parameters of \(p\).

In this case the free energy \(F(x)\) from Equation (2) (now independent of time) takes the form,

\[\begin{align*} F(x; \theta, z) &= \mathbb{E}_{q(s\mid x)}[-\log p(s) - \log p(x\mid s)] = -\log p(z_L) - \sum_{l=1}^{L} \log p(z_{l-1}\mid z_l)\\ &= \frac{1}{2} (z_L - \hat{\mu})^T \hat{\Sigma}^{-1} (z_L - \hat{\mu}) + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{l=1}^{L} (z_{l-1} - \mu_l(z_l))^T \Sigma_l^{-1} (z_{l-1} - \mu_l(z_l))\\ &+ \frac{1}{2} \log \mid 2\pi\hat{\Sigma}\mid + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{l=1}^{L} \log \mid 2\pi\Sigma_l\mid \end{align*}\]where \(z_0 \equiv x\).

The variational EM algorithm (neglecting amortized inference for now) consists of:

- Iterative inference: update \(z\) via gradients

\(\frac{\partial F}{\partial z_l} = \begin{cases} \Sigma_{l+1}^{-1} \epsilon_l - \left[\frac{\partial \mu_l(z_l)}{\partial z_l}\right]^T \Sigma_l^{-1} \epsilon_{l-1}, & l = 1, \ldots, L-1\\ \hat{\Sigma}^{-1} \epsilon_L - \left[\frac{\partial \mu_L(z_L)}{\partial z_L}\right]^T \Sigma_L^{-1} \epsilon_{L-1}, & l = L \end{cases}\) where we have defined \(\epsilon_l := z_l - \mu_{l+1}(z_{l+1})\) (for \(l < L\)) and \(\epsilon_L := z_L - \hat{\mu}\).

- Learning: update \(\theta\) via the gradients

This update process is local, and hence biologically plausible, since each update of \(z_l\) only depends on locally accessible information of its children nodes (in this case, \(z_{l-1}\)).

- This locality contrasts with conventional backpropagation. For example, under conventional backpropagation, a single update step for the weight of the first layer requires access to the weight of the final layer – such non-local dependence is not present in predictive coding.

We can extend the above to include amortized inference, where upon receiving \(x\) we compute some initialization value for the neural activity \(z\), and from there perform iterative inference. We can interpret the typical models in machine learning, e.g. transformers, as solely performing such an amortized inference stage, without performing any iterative inference explicitly. However, one can argue that the residual structure of modern architectures, such as transformers, allows one to simulate an iteriative inference-like process. Indeed, they basically take the same form,

\(\text{Residual structure:} \; \; \; z^{(l+1)} = z^{(l)} + f_{l+1}(z^{(l)}) \; \; \; \text{at layer} \; l\) \(\text{Explicit iterative inference:} \; \; \; z^{(n+1)} = z^{(n)} - \eta \frac{\partial F(z^{(n)})}{\partial z} \; \; \; \text{at time-step} \; n\)

That is, we can potentially think of iterative inference as taking place implicitly over the layers of a residual architecture (like a transformer), whereas in the brain/predictive coding, it takes place over time via backward connections. This justifies why we may expect transformers to have to be much deeper than the brain; the brain’s recurrent/backward connections are roughly analogous to a deeper, strictly feedforward residual architecture.

The above presentation of predictive coding has neglected two aspects: temporality, and action selection. Our general framework naturally extends to include these two aspects, as we will show below.

Neuro interpretation. One perspective highlighted by [13] is that to understand biological intelligence, one should first develop a computational/algorithmic description of cognition, and only then should one consider how such an algorithm could be implemented neurally. Ambitiously, such an approach would shed light on why the brain has the structure and properties that it does. In this vein, we can make the following rough analogies to the brain:

- \(z_t^n\) as the state of the \(n\)th cortical column, with \(z_t\) the state of the cortex (unsure whether this would include the prefrontal cortex, which may operate by different principles (e.g. not simply predictive coding) compared to e.g. the sensory cortex?).

- Amortized inference as initial feedforward sweep of neural activity (as described in [7]).

- The iterative inference stage as a phase of local communication between cortical columns, eventually converging to some agreement \(z_t\). Agrees with cortical uniformity, with each cortical column employing the same local algorithm for communication and updates.

- Relation to basal ganglia: dorsal striatum embodies \(\hat{Q}(s_t, a_t)\), and ventral striatum embodies \(\hat{V}(s_t)\), with \(s_t\) received by striatum via projections from cortex.

- Standard interpretation of dopamine from midbrain as communicating reward-related errors, facilitating updating of \(\hat{V}\) and \(\hat{Q}\) via projections to basal ganglia, and potentially the computation of gradient \(\nabla_{\phi} V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s)\).

- Hippocampus acting as a replay buffer, useful for sampling past \((s, a, s') \in \mathcal{D}\) (for training world model \(p\) and estimates \(\hat{Q}\), \(\hat{V}\)).

- Adding compositional structure to reward function, in the sense of “Reward Bases” [12], could model context-dependent dynamic values, and adaptive behaviour.

- Something like the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop as facilitating the computation of \(\nabla_{\phi} Q_{\pi_{\phi}}(s, a)\) and \(\nabla_{\theta} V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s)\) for updating the policy and world model respectively? (i.e. basal ganglia needs state \(s\) from cortex, and cortex needs information about how \(Q_{\pi_{\phi}}\) and \(V_{\pi_{\phi}}\) vary wrt \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) from the basal ganglia)

References

[1] Levine, S. (2018). Reinforcement learning and control as probabilistic inference: Tutorial and review.

[2] Millidge, B. (2020). Deep active inference as variational policy gradients.

[3] Ha, D., & Schmidhuber, J. (2018). World models.

[4] McCloskey, M., & Cohen, N. J. (1989). Catastrophic interference in connectionist networks: The sequential learning problem.

[5] Lillicrap, T. P., Santoro, A., Marris, L., Akerman, C. J., & Hinton, G. (2020). Backpropagation and the brain.

[6] Song, Y., Millidge, B., Salvatori, T., Lukasiewicz, T., Xu, Z., & Bogacz, R. (2024). Inferring neural activity before plasticity as a foundation for learning beyond backpropagation.

[7] Tscshantz, A., Millidge, B., Seth, A. K., & Buckley, C. L. (2023). Hybrid predictive coding: Inferring, fast and slow.

[8] Alonso, N., Millidge, B., Krichmar, J., & Neftci, E. O. (2022). A theoretical framework for inference learning.

[9] Friston, K., Schwartenbeck, P., FitzGerald, T., Moutoussis, M., Behrens, T., & Dolan, R. J. (2013). The anatomy of choice: active inference and agency.

[10] Millidge, B., Tschantz, A., & Buckley, C. L. (2021). Whence the expected free energy?

[11] Champion, T., Bowman, H., Marković, D., & Grześ, M. (2024). Reframing the Expected Free Energy: Four Formulations and a Unification.

[12] Millidge, B., Walton, M., & Bogacz, R. (2022). Reward bases: Instantaneous reward revaluation with temporal difference learning.

[13] Marr, D. (1982). Vision: A computational investigation into the human representation and processing of visual information.

Appendix: Reinforcement learning background

Given Equation (1), the term (c) in Equation (2) can be written

\[\begin{align*} &\sum_{\tau=1}^{t-1} \mathbb{E}_{q(\pi\mid s_{\tau}) q(s_{\tau}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[-\log p(\pi\mid s_{\tau})]\\ &= -\beta \sum_{\tau=1}^{t-1} \mathbb{E}_{q(\pi\mid s_{\tau}) q(s_{\tau}\mid x_{1:t}, a_{<t})}[V_{\pi}(s_{\tau})] \end{align*}\]If we choose \(q(\pi\mid s_{\tau}) = \delta(\pi-\pi_{\phi})\), then we essentially arrive at the problem of:

\[\text{maximize} \; V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_t) \; \text{with respect to} \; \phi\]which is exactly the goal of policy-based reinforcement learning (RL). Recall that,

\[V_{\pi}(s_t) = \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi)}\left[\sum_{\tau=t}^{T} \gamma^{\tau-t} R(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau})\right],\] \[Q_{\pi}(s_t, a_t) = \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{>t}\mid s_t, a_t, \pi)}\left[\sum_{\tau=t}^{T} \gamma^{\tau-t} R(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau})\right]\]and note that

\[V_{\pi}(s) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi(a\mid s)}[Q_{\pi}(s, a)], \quad Q_{\pi}(s, a) = R(s, a) + \gamma \mathbb{E}_{p(s'\mid s, a)}[V_{\pi}(s')]\]There appears to be two notable methods for performing credit assignment in RL: (a) policy gradient methods (e.g. REINFORCE, PPO) (b) amortized gradient methods (e.g. DQN, DDPG, SVG(0), SAC). Both involve gradient ascent using gradient \(\nabla_{\phi} V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_t)\), yet utilize different expressions for this gradient. As a quick summary,

a) Policy gradient methods consider writing the gradient in the form,

\[\nabla_{\phi} V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_t) = \sum_{\tau=t}^{\infty} \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[\Phi_{t, \tau} \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})]\]with various choices of \(\Phi_{t, \tau}\), typically involving approximations \(\hat{V} \approx V_{\pi_{\phi}}\) and/or \(\hat{Q} \approx Q_{\pi_{\phi}}\), described in more detail below.

b) Amortized gradient methods instead consider the form,

\[\nabla_{\phi} V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_t) \approx \nabla_{\phi} \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\phi}(a_t\mid s_t)}[\hat{Q}(s_t, a_t)]\]for an approximation \(\hat{Q} \approx Q_{\pi_{\phi}}\) or \(Q_{\pi_{*}}\) (for optimal policy \(\pi_{*}\)). In most contexts we can write \(a_t = f_{\phi}(s_t, \epsilon)\) under \(a_t \sim \pi_{\phi}(a_t\mid s_t)\) for random variable \(\epsilon \sim p(\epsilon)\), and hence via the reparameterization trick we can write

\[\nabla_{\phi} V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_t) \approx \mathbb{E}_{p(\epsilon)}[\nabla_{\phi} \hat{Q}(s_t, f_{\phi}(s_t, \epsilon))]\]As an example of what \(f_{\phi}\) may look like in practice, for a Gaussian policy:

\[\pi_{\phi}(a_t\mid s_t) = \text{N}(a_t; \mu_{\phi}(s_t), \Sigma_{\phi}(s_t))\] \[\implies a_t = f_{\phi}(s_t, \epsilon) = \mu_{\phi}(s_t) + \epsilon U_{\phi}(s_t), \; \; \; \text{where} \; \; \Sigma_{\phi}(s_t) = U_{\phi}(s_t) U_{\phi}(s_t)^{T}\]for \(\epsilon \sim \text{N}(0, I)\).

Amortized gradient methods. Examples of amortized gradient methods:

-

DQN corresponds to the amortized method, however since its in the context of (small) discrete action spaces, the optimal action

\[a^{*}(s) = \text{argmax}_a \hat{Q}(s, a)\]can be computed directly. Further, as in Q-learning, \(\hat{Q} \approx Q_{\pi_{*}}\) where \(\pi_{*}\) is the optimal policy, satisfying the Bellman equation,

\[Q_{\pi_{*}}(s, a) = \mathbb{E}_{p(s'\mid s, a)}[R(s, a) + \gamma \max_{a'} Q_{\pi_{*}}(s', a')]\]where we minimize the associated greedy SARSA-like loss,

\[\frac{1}{2} \mathbb{E}_{p(s, a, s'\mid \pi_{a^{*}})}[(\hat{Q}(s, a) - (R(s, a) + \gamma\max_{a'} \hat{Q}(s', a'))^2]\]to obtain \(\hat{Q} \approx Q_{\pi_{*}}\).

-

DDPG extends Q-learning/DQN to continuous action spaces using the amortized method, restricting to deterministic policies \(\pi_{\phi}(a\mid s) = \delta(a - \mu_{\phi}(s))\), hence with corresponding gradient,

\[\nabla_{\phi} V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_t) \approx \nabla_{\phi} \hat{Q}(s_t, \mu_{\phi}(s_t))\]and approximating \(\hat{Q} = Q_{\pi_{*}}\) equivalently to DQN.

-

The SVG(0) algorithm is an extension of DDPG for stochastic policies \(\pi_{\phi}\), by utilizing the reparameterization trick (demonstrated above in (b)). It approximates \(\hat{Q} \approx Q_{\pi_{\phi}}\) (i.e. not under the optimal policy, unlike DDPG) using a SARSA-like objective,

\[\frac{1}{2} \mathbb{E}_{p(s, a, s', a'\mid \pi_{\phi})}[(\hat{Q}(s, a) - (R(s, a) + \gamma\hat{Q}(s', a'))^2]\] -

SAC extends SVG(0) to include an entropy term, and also uses a value network alongside the action-value network. They found that the value network improved training stability. The objectives considered for training \(\hat{V} \approx V_{\pi_{\phi}}\) and \(\hat{Q} \approx Q_{\pi_{\phi}}\) are

\[\frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}_{p(s)}[(\hat{V}(s) - \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\phi}(a\mid s)}[\hat{Q}(s, a) \underbrace{- \log \pi_{\phi}(a\mid s)}])^2],\] \[\frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}_{p(s, a\mid \pi_{\phi})}[(\hat{Q}(s, a) - (R(s, a) + \gamma\mathbb{E}_{p(s'\mid s, a)}[\hat{V}(s')]))^2]\]respectively. The reason why \(\hat{V}\)’s objective has an entropy term yet \(\hat{Q}\)’s doesnt, is because SAC defines the value \(V_{\pi_{\phi}}\) to include an entropy term.

Policy gradient methods. For the return \(G_t := \sum_{\tau=t}^{\infty} \gamma^{\tau-t} R(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau})\), note that

\[V_{\pi_\phi}(s_t) = \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_\phi)}[G_t]\] \[\implies \nabla_{\phi} V_{\pi_\phi}(s_t) = \sum_{\tau=t}^{\infty} \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_\phi)}[G_t \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})]\]We can approximate this via a (truncated) Monte Carlo method over trajectory information, however if the trajectory information is taken under an older policy \(\pi_{\phi_{old}}\), we should instead include a ratio factor:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_\phi)}[G_t \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})] &= \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi_{old}})}\left[\frac{\pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})}{\pi_{\phi_{old}}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})} G_t \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})\right]\\ &= \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi_{old}})}\left[G_t \frac{\nabla_{\phi} \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})}{\pi_{\phi_{old}}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})}\right] \end{align*}\]We can write \(\nabla_{\phi} V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_t)\) in a more general form by manipulating the expectance, or including a baseline. Specifically, we can write

\[\nabla_{\phi} V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_t) = \sum_{\tau=t}^{T} \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[\Phi_{t, \tau} \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})]\]for a variety of choices of \(\Phi_{t, \tau}\):

- \(\Phi_{t, \tau} = G_t\).

- \(\Phi_{t, \tau} = G_{\tau} = \sum_{\tau'=\tau}^{T} R(s_{\tau'}, a_{\tau'})\).

- \(\Phi_{t, \tau} = G_{\tau} - b(s_{\tau})\), e.g. \(b = \hat{V} \approx V_{\pi_{\phi}}\).

- \(\Phi_{t, \tau} = Q_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau})\).

- \(\Phi_{t, \tau} = Q_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}) - V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_{\tau})\) (advantage), which is just (4) with a baseline (3).

- \(\Phi_{t, \tau} = R(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}) + \gamma R(s_{\tau+1}, a_{\tau+1}) + \cdots + \gamma^T R(s_{\tau+T}, a_{\tau+T}) + V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_{\tau+T+1}) - V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_{\tau})\).

(2) and (3) follow from (1) because, for an arbitrary function \(f = f(s_{\leq \tau}, a_{<\tau})\),

\[\mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[f(s_{\leq \tau}, a_{<\tau}) \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})] = 0\]for \(\tau \geq t\). (4) holds because,

\[\begin{align*} &\mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[G_{\tau} \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})] = \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{\geq\tau}, a_{\geq \tau}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[G_{\tau} \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})]\\ &= \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})} \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>\tau}, a_{>\tau}\mid s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}, \pi_{\phi})}[G_{\tau} \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})]\\ &= \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[(R(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}) + \underbrace{\mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>\tau}, a_{>\tau}\mid s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}, \pi_{\phi})}[\gamma R(s_{\tau+1}, a_{\tau+1}) + \cdots]}_{= Q_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}) - R(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau})}) \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})]\\ &= \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[Q_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}) \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})] \end{align*}\](6) follows from (5), using

\[\begin{align*} Q_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}) &= R(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}) + \gamma \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{\tau+1}, a_{\tau+1}\mid s_{\tau}, a_{\tau})}[R(s_{\tau+1}, a_{\tau+1})] + \cdots\\ &+ \gamma^T \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>\tau}, a_{>\tau}\mid s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}, \pi_{\phi})}[R(s_{\tau+T}, a_{\tau+T})] + \gamma^{T+1} \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>\tau}, a_{>\tau}\mid s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}, \pi_{\phi})}[V_{\pi_{\phi}}(s_{\tau+T+1})] \end{align*}\]Examples of policy gradient methods:

- REINFORCE uses choice (2) for \(\Phi_{t, \tau}\). However this suffers from high variance, so in practice one typically uses a baseline, such as choice (3).

- PPO uses a GAE (generalized advantage estimator) variant of choice (6). We describe GAE below.

GAE estimator. Recall the return

\[G_{\tau} = \sum_{t=\tau}^{\infty} \gamma^{t-\tau} R(s_{t}, a_{t})\]We will define the truncated return,

\[G_{\tau}^{(n)} := \sum_{t=\tau}^{\tau+n-1} \gamma^{t-\tau} R(s_t, a_t) + \gamma^n V(s_{\tau+n})\]We then consider the exponential moving-average,

\[G_{\tau}(\lambda) := (1-\lambda)(G_{\tau}^{(1)} + \lambda G_{\tau}^{(2)} + \lambda^2 G_{\tau}^{(3)} + \cdots)\]Note that \(\lambda = 1\) corresponds to the entire return \(G_{\tau}\), whereas \(\lambda = 0\) corresponds to using the one-step return \(G_{\tau}^{(1)} \equiv R(s_{\tau}, a_{\tau}) + \gamma V(s_{t+1})\). Then we can view \(\lambda \in [0, 1]\) as balancing the tradeoff between bias and variance (\(\lambda=0\) is min variance but high bias, and vice-versa for \(\lambda=1\)).

We should view \(G_{\tau}(\lambda)\) as a drop-in approximation for \(G_{\tau}\). This is valid because

\[\mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[G_{\tau}^{(n)} \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})] = \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[G_{\tau} \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})]\]such that

\[\mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[G_{\tau}(\lambda) \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})] = \mathbb{E}_{p(s_{>t}, a_{\geq t}\mid s_t, \pi_{\phi})}[G_{\tau} \nabla_{\phi} \log \pi_{\phi}(a_{\tau}\mid s_{\tau})]\]as required, using \(1+\lambda+\lambda^2+\cdots = 1/(1-\lambda)\).

Using \(G_{\tau}(\lambda)\) in-place of the return \(G_{\tau}\) for TD-learning results in the TD\((\lambda)\) algorithm.

In the context of advantage baselines, we instead consider an exponential moving-average over advantages, rather than returns. Specifically, we define the truncated advantage

\[\begin{align*} A_{\tau}^{(n)} &:= G_{\tau}^{(n)} - V(s_{\tau})\\ &= \sum_{t=\tau}^{\tau+n-1} \gamma^{t-\tau} R(s_t, a_t) + \gamma^n V(s_{\tau+n}) - V(s_{\tau}) \end{align*}\]and define the GAE (generalized advantage estimator) as an exponential moving-average,

\[A_{\tau}(\lambda) := (1-\lambda)(A_{\tau}^{(1)} + \lambda A_{\tau}^{(2)} + \lambda^2 A_{\tau}^{(3)} + \cdots)\]which, by defining \(\delta_t := R(s_t, a_t) + \gamma V(s_{t+1}) - V(s_t)\), we can write as

\[\begin{align*} A_{\tau}(\lambda) &= (1-\lambda)(\delta_{\tau} + \lambda(\delta_{\tau} + \gamma \delta_{\tau+1}) + \lambda^2(\delta_{\tau} + \gamma \delta_{\tau+1} + \gamma^2 \delta_{\tau+2}) + \cdots)\\ &= (1-\lambda)\underbrace{(1 + \lambda + \lambda^2 + \cdots)}_{1/(1-\lambda)}(\delta_{\tau} + (\gamma\lambda) \delta_{\tau+1} + (\gamma\lambda)^2 \delta_{\tau+2} + \cdots)\\ &= \sum_{t=\tau}^{\infty} (\gamma\lambda)^{t-\tau} \delta_{t} \end{align*}\]PPO considers a truncated form of GAE

\[A_{\tau}(\lambda, T) = (1-\lambda)(A_{\tau}^{(1)} + \lambda A_{\tau}^{(2)} + \cdots + \lambda^{T-1} A_{\tau}^{(T)})\]But it seems this has not been corrected for bias-correction, which would instead correspond to

\[\tilde{A}_{\tau}(\lambda, T) = \frac{1-\lambda}{1-\lambda^T} (A_{\tau}^{(1)} + \lambda A_{\tau}^{(2)} + \cdots + \lambda^{T-1} A_{\tau}^{(T)})\]though perhaps this is negligible in practice.